Have you ever heard of the 10,000-hour rule? It is a concept that appears throughout Malcolm Gladwell’s book, “Outliers” published in 2008.

The ten thousand hours rule is based on the research of Anders Ericsson, who studied expert performance and domains such as medicine, music, chess, and sports, focusing exclusively on extended deliberate practice as a means of how expert performers acquire their superior performance. In the book, Gladwell states, “ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness”.

Gladwell claims that greatness requires enormous amounts of time, using the talents of The Beatles and Bill Gates’ computer savvy as examples. He explained that to achieve this milestone, which he considered to be the key to success in any field, you simply need to practice a specific task 3 hours a day for ten years.

As an example of this ten thousand hours rule, Gladwell cites the Beatles in Hamburg, Germany; over 1200 performances from 1960 to 1964, amassing more than ten thousand hours of playing time, therefore, meeting the ten thousand hours rule. Bill Gates amassed ten thousand hours when he got access to a high school computer in 1968 at the age of 13 spending the ten thousand hours learning to program before he started Microsoft.

In 1993, Anders Ericsson, Ralf Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Romer did a study on a group of violin students in Berlin. According to the results, the study found that the most accomplished of those students put in an average of ten thousand hours of practice by the time they were twenty years old. That paper would go on to become a major part of the scientific literature on expert performers, but it was not until 2008, with the publication of “Outliers,” that the paper’s results attracted much attention outside the scientific community.

Now, Ericsson and co-author Robert Pool have a new book coming out called, Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. They recently laid out some of its main points in an article for Salon, where they pointed out the fundamental flaws with the 10,000-hour rule:

Mastery

by Robert Greene

⏱ 11 minutes reading time

🎧 Audio version available

First off, Ericsson and Pool stated, “The rule is irresistibly appealing. It’s easy to remember, for one thing. It would’ve been far less effective if those violinists had put in, say, eleven thousand hours of practice by the time they were twenty. And it satisfies the human desire to discover a simple cause-and-effect relationship: just put in ten thousand hours of practice at anything, and you will become a master.”

While explaining their study in detail they argued, “First, there is nothing special or magical about ten thousand hours. Gladwell could just as easily have mentioned the average amount of time the best violin students had practiced by the time they were eighteen (approximately seventy-four hundred hours). But he chose to refer to the total practice time they had accumulated by the time they were twenty because it was a nice round number.

And, either way, at eighteen or twenty, these students were nowhere near masters of the violin. They were very good, promising students who were likely headed to the top of their field, but they still had a long way to go at the time of the study. Pianists who win international piano competitions tend to do so when they’re around thirty years old, and thus they’ve probably put in about twenty to twenty-five thousand hours of practice by then; ten thousand hours is only halfway down that path.”

“Second, the number of ten thousand hours at age twenty for the best violinists was only an average. Half of the ten violinists in that group hadn’t accumulated ten thousand hours at that age. Gladwell misunderstood this fact and incorrectly claimed that all the violinists in that group had accumulated over ten thousand hours.”

“Third, Gladwell didn’t distinguish between the type of practice that the musicians in our study did — a very specific sort of practice referred to as “deliberate practice” which involves constantly pushing oneself beyond one’s comfort zone, following training activities designed by an expert to develop specific abilities, and using feedback to identify weaknesses and work on them — and any sort of activity that might be labeled “practice.”

Ericsson and Pool also stated their view on what their research suggests.

“In pretty much any area of human endeavor, people have a tremendous capacity to improve their performance, as long as they train in the right way. If you practice something for a few hundred hours, you will almost certainly see great improvement (it took Steve Faloon only a couple of hundred hours of practice to become the best at memorizing strings of digits) but you have only scratched the surface. You can keep going and going and going, getting better and better and better. How much you improve is up to you.”

After Anders Ericson’s book “Outliers” was published, experts started criticizing it by calling it a big foul. As the Guardian pointed out in 2012:

“There is nothing magical about the 10,000 figure, as Ericsson said recently because the best group of musicians had accumulated an average, not a total, of over 10,000 hours by the age of twenty. In the world of classical music, it seems that the winners of international competitions are those who have put in something like 25,000 hours of dedicated, solitary practice – that’s three hours of practice every day for more than 20 years.”

“Ericsson is also on record as emphasizing that not just any old practice counts towards the 10,000-hour average. It has to be deliberate, dedicated time spent focusing on improvement.”

According to a psychologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, “When it comes to human skill, a complex combination of environmental factors, genetic factors, and their interactions explain the performance differences across people. And, when the human body is put under exceptional strain during deliberate practice, a range of dormant genes in the DNA of any healthy individual are expressed, and extraordinary physiological processes are activated. The benefit of this type of practice is available to anyone who wants to improve their performance.”

Forty years ago, in a paper in American Scientist, Herbert Simon and William Chase drew one of the most famous conclusions:

“There are no instant experts in chess—certainly no instant masters or grandmasters. There appears not to be on record any case where a person reached grandmaster level with less than about a decade’s intense preoccupation with the game. We would estimate, very roughly, that a master has spent perhaps 10,000 to 50,000 hours staring at chess positions”.

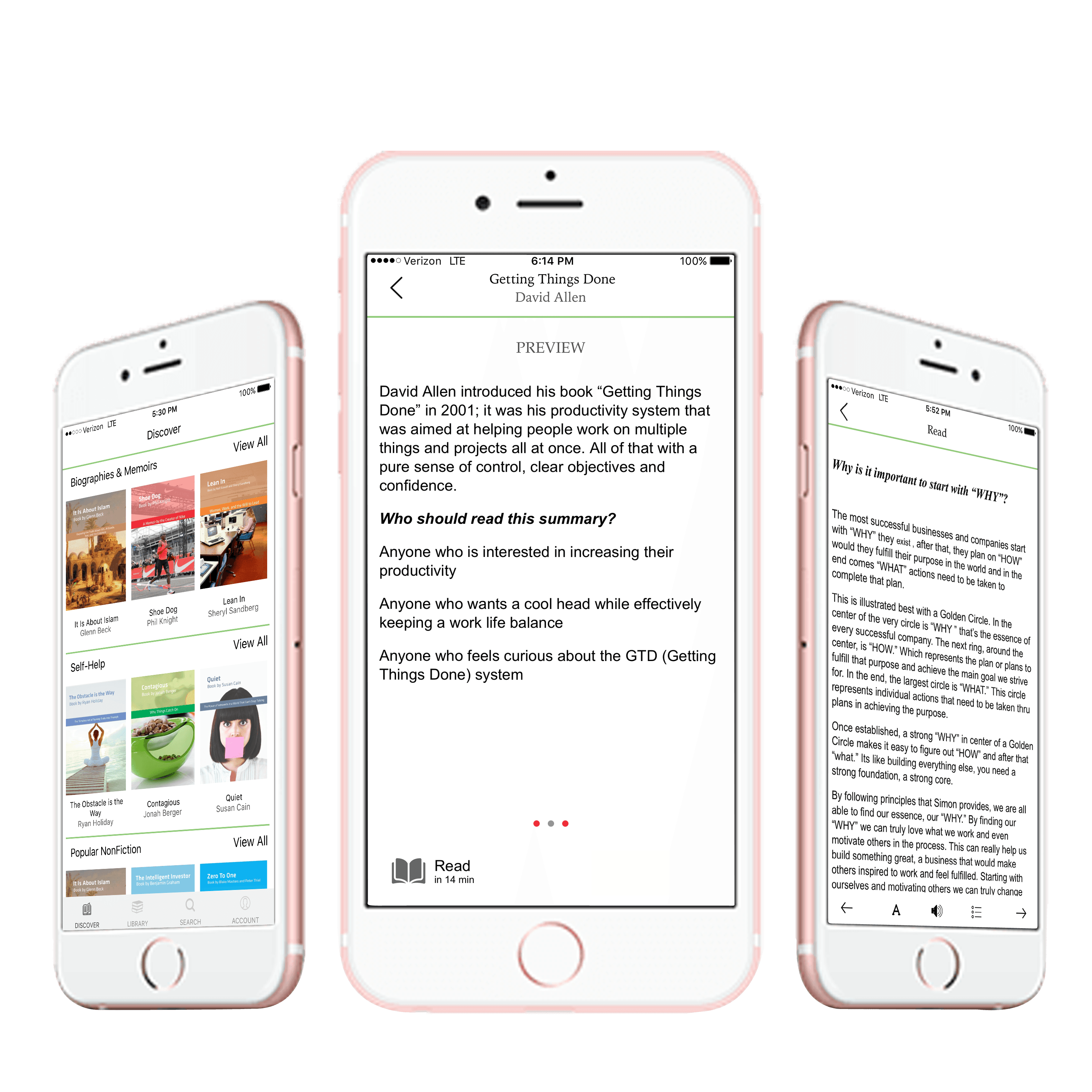

What Is Snapreads?

With the Snapreads app, you get the key insights from the best nonfiction books in minutes, not hours or days. Our experts transform these books into quick, memorable, easy-to-understand insights you can read when you have the time or listen to them on the go.